By Joanne Kurtzberg, MD

Jerome Harris Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics Professor of Pathology

Director, Marcus Center for Cellular Cures

Director, Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Program

Director, Carolinas Cord Blood Bank

Co-Director, Stem Cell Transplant Laboratory Duke University Medical Center

Matthew Farrow (Matt) was born with a serious and fatal genetic disease called Fanconi Anemia. Children with this disease have a genetic mutation that interferes with the process by which their cells repair DNA during cell division. Affected individuals have an increased risk of certain cancers and also develop bone marrow failure in the first decade of life. They can also have a variety of symptoms including short stature, a single kidney, absent or extra fingers or toes, deformities of the hips or spine, and congenital heart disease.

Matt was born in 1983 and did well for his first 2 years of life. He then developed low blood counts and was referred to Duke University, where he was diagnosed with Fanconi Anemia. He was supported with transfusions of red blood cells, platelets, and antibiotics for the first few months after diagnosis while a search for a donor for a hematopoietic (blood-forming) stem cell transplant, the only curative therapy for Fanconi Anemia, was undertaken.

Matthew’s mother was pregnant with another baby at the time of his diagnosis. The fetus was tested in utero and found to be a healthy, perfect match for Matthew. The testing was performed by Dr. Arleen Auerbach, a researcher at the Rockefeller Institute. Dr. Auerbach first described the molecular defects in Fanconi Anemia, developed a test to diagnosis patients, and created a registry of patients diagnosed with this rare disease. Dr. Auerbach worked with Dr. Hal Broxmeyer, who had just discovered that cord blood contained blood stem and progenitor cells. Together they hypothesized that cord blood from a matched sibling donor could be collected, banked, and later used for a transplant to treat an affected sibling.

Matthew’s case presented the perfect circumstance to test whether cord blood could be used as a donor for transplantation. Arrangements were made to collect the cord blood when Matthew’s sister was born. The cord blood was shipped to Dr. Broxmeyer’s lab, where it was frozen and placed in liquid nitrogen for long term preservation of stem cells. Arrangements were made for Matthew, his sister and their parents to travel to Paris, France where, at Hôpital Saint-Louis, Dr. Eliane Gluckman performed his transplant. Dr. Broxmeyer flew the cells to France in a special shipper to keep them at ultra-cold temperatures. In 1988, Dr. Gluckman had more experience transplanting patients with Fanconi Anemia than anyone in the world. Matthew’s body accepted his sister’s cells after the transplant without complications. He and his family came back to their home in North Carolina six months later and resumed his care at Duke. The transplant program at Duke had not yet been established.

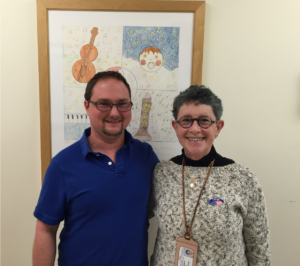

Matthew is now 38 years old. He lives and works independently. Despite some chronic health problems related to his Fanconi Anemia, he is doing reasonably well.

Matthew’s transplant from a matched sibling was the first cord blood transplant in the world. It proved that cord blood contains blood stem cells and that cord blood can be used as donor blood-forming cells for transplantation. After Matthew’s transplant in 1988, unrelated donor cord blood registries and banks were established. Duke opened its transplant program in 1990 and in 1993, performed the first unrelated cord blood transplant in the world for a 4-year-old boy with leukemia. Over the past three decades, cord blood banking and transplantation have emerged as well-established fields, and cord blood has proven its role as donor blood-forming cells for transplantation in patients lacking a matched donor in their family.