“I definitely had to learn very early that I was different than everybody else. And it wasn’t so much that I couldn’t play with everybody else or do things like that, just kind of learning how to do it with my sickle cell,” says Kelvin Brown.

“I definitely had to learn very early that I was different than everybody else. And it wasn’t so much that I couldn’t play with everybody else or do things like that, just kind of learning how to do it with my sickle cell,” says Kelvin Brown.

One in every 365 African American children are born with sickle cell disease (SCD), a painful and disabling condition that damages organs, joints and other tissues, and significantly increases the risk of infection and stroke. Normal red blood cells are round, tumbling through small blood vessels to deliver oxygen to all tissues of the body. Someone with SCD, however, produces C-shaped, or “sickle” shaped red blood cells. Instead of tumbling, these hard, sticky cells clog up in small blood vessels. When the flow of oxygen is interrupted, organs and tissues are damaged and patients experience episodes of extreme pain that can last for days.

According to Kelvin’s mother, Sharon, “We would describe it like a silent disease. He looks normal, so people take it for granted that he’s fine, but sickle cell is real.”

Because all blood cells are produced in bone marrow, SCD can be cured by a bone marrow stem cell transplant.

Sickle cell trait (possessing only one of the two genes needed to have SCD) is protective against malaria, and SCD is most commonly diagnosed in people whose ancestors came from places where malaria was common: sub-Saharan Africa, Saudi Arabia, India and the Mediterranean countries.

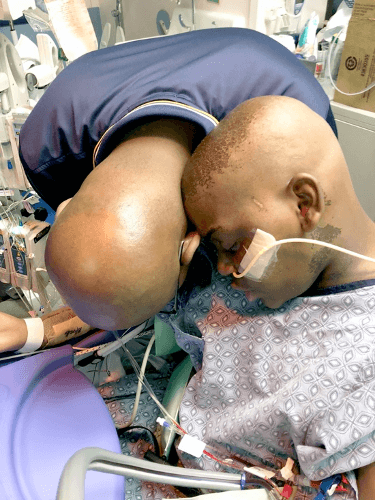

Blood transfusions and treatment with drugs that prevent infection, relieve pain, and minimize organ damage help people with SCD manage their disease. After age 14, however, Kelvin’s pain crises became unbearable and his doctor recommended a bone marrow stem cell transplant.

Fortunately, the Pediatric Transplant and Cellular Therapy (PTCT) program at Duke University had an opening for Kelvin in a clinical trial using 2 umbilical cord blood units from unrelated donors to treat SCD. Umbilical cord blood cells collected after the birth of a baby and donated by parents to a cord blood bank are, like bone marrow, a rich source of normal blood-forming stem cells.

Kelvin’s transplant was successful and he is now cured of SCD, but the damage already done to his body was extensive. He’s currently on a waiting list for a kidney transplant and recently had hip and shoulder replacement surgeries.

The financial hardship that prevents many families from participating in potentially life-saving clinical trials is the reason the National Stem Cell Foundation (NSCF) established a Patient Advocacy Fund at PTCT. We help cover insurance deductibles and co-pays so families can focus on what matters most: their child’s health.

According to Sharon, “It has been a huge support for families like myself, so I will be eternally grateful for all the things you guys… provide to families.”

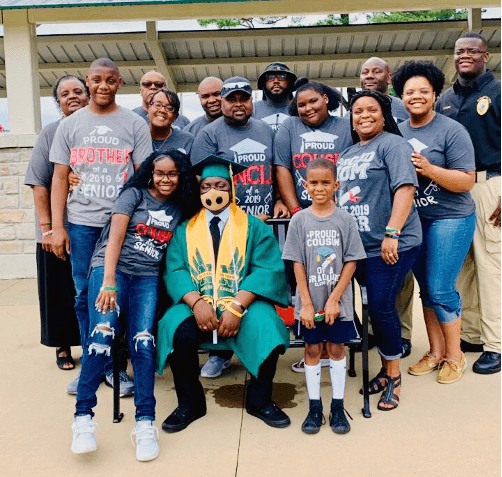

Kelvin graduated from high school with honors in 2019 and is now taking computer-aided drafting courses at College of The Albemarle.

Kelvin is still waiting to find a match for a living donor kidney transplant. If you or someone you know is blood type O+ and interested in being screened as a donor for Kelvin, call the Duke Transplant Center at 919-613-7777.

Children from around the U.S. and all over the world travel to PTCT for access to cutting-edge clinical trials for rare childhood disorders. Kelvin is one of more than a hundred children helped by the NSCF Patient Advocacy Fund there.

Donations help cover the cost of insurance deductibles and co-pays for families like his. To learn more about the program click here.